Paris had been broken, Paris had been martyred, but Paris had been liberated. This all happened 70 years ago – a lifetime. Roland-Garros picked up again after a six-year hiatus due to the Second World War, and the first tournament in the post-war era was a special moment, with players and spectators uniting. It was a renaissance – a time for happiness after so much horror. Relive this glorious chapter in the tournament’s history.

The Liberation of Roland-Garros

1946: a renaissance for Paris, and for Roland-Garros, after a 6-year hiatus due to World War II.

"The French people headed back to Roland-Garros stadium. Having been deprived of sporting entertainment during the war, they intended to make up for lost time. They turned out in numbers, because due to the rationing of petrol, journeying beyond the Île-de-France, beyond the greater Paris area, was but a pipe dream." - July 1946.

Like many others, Bernard Destremeau put his uniform aside and returned to what had been his everyday life before six years of war and occupation changed things significantly. Not that he threw the uniform away. "At the time, you had to make do and mend, and we were certainly pleased to use the army-issue shorts as we had nothing else to wear!" smiled American legend Budge Patty.

Now 94, the oldest surviving winner of Roland-Garros - Patty won his title in 1950 - has forgotten nothing from his first time in Paris. "I experienced the liberation in Paris as a soldier in the 5th Army returning from Italy. I returned to the United States in January 1946... and soon hurried back here five months later! I was 18 and wanted to be grown up, to study – I was actually heading to university when I got my mobilisation orders. But after the war, you couldn’t hope to do that anymore. I lost two years of my life because of the war, and like all the young people in my generation, I had lots of things to catch up on."

Roland-Garros 1950 champ: Budge Patty

The youngsters were not the only ones wanting to live life to the full in the months immediately following the war, and all the various sporting events turned into huge popular gatherings. At the Davis Cup a few weeks earlier, 2,000 people were locked out of a full-to-capacity Roland-Garros stadium to see former stars Yvon Pétra, Marcel Bernard and Destremeau. Then, at Roland-Garros on 7 July, 10,000 spectators gathered to cheer on boxer Marcel Cerdan in his bout with the American Holmann Williams.

Paris, a moveable feast for the G.I.s still here in 1946

"There were still lots of G.I.s in Paris in 1946, and they were all looking for any kind of entertainment," explains Destremeau in his memoirs, entitled ‘The Fifth Set’. "For them it was a double celebration – it was the end of the war and the discovery of the famous ‘vie parisienne’, even if it was the Paris of the post-occupation era." Budge Patty was among those happy to take what was on offer. He "fell in love with Paris immediately", to such an extent that he ended up acquiring an apartment on the banks of the Seine.

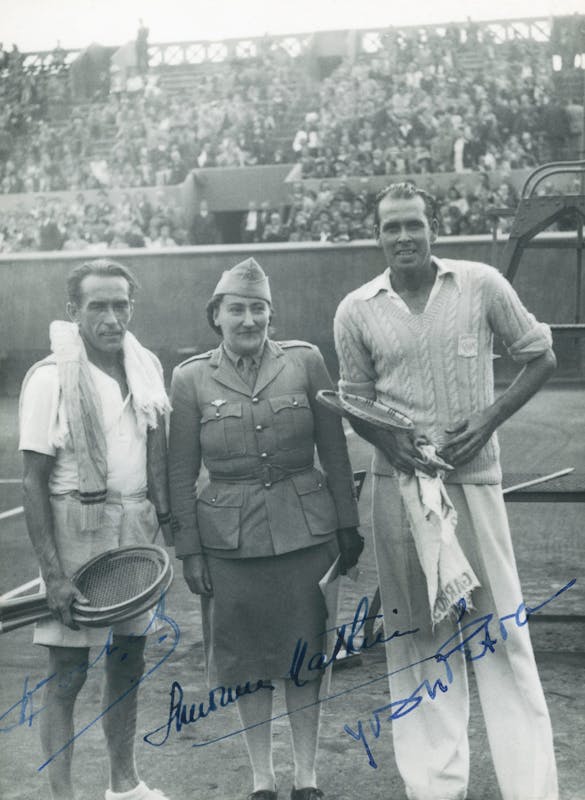

17th September 1944: the first tennis match to be played in liberated Paris, an exhibition between Henri Cochet and Yvon Petra. The umpire is former Roland-Garros champ Simonne Mathieu, in her French Free Forces captain’s uniform.

As an exception that year, Roland-Garros and Wimbledon swapped places in the calendar. A mere detail? Far from it – it ended up making history. Due to the incredible heat throughout the tournament – and since the times, they were a-changing as well – the players were allowed to observe shirt-sleeve order… and what is more, to wear shorts, which had never been widely accepted, despite making an original appearance back in the 1930s.

But the arrival of a new generation of players, combined with the stormy skies above France during the summer of 1946, meant that conventions were thrown out of the window. The youngsters were more inclined to wear shorts than their elders, but the latter ended up slowly but surely adopting the trend – Marcel Bernard for example was in trousers during the week, then opted for shorts in the final of the singles, only to prefer trousers once again the following day for the doubles championship match!

"Some players were almost passing out by the end of their matches"

The 1946 French Open began on 18 July, in front of a massive crowd which was looking to pick things up where they had left off in September 1939, regardless of the stark change in fortunes. "The first big tournaments post-war were played in conditions that one cannot imagine," said Destremeau. "We struggled to find clothes to wear, and to get enough to eat, and there were times when we had to make do with some outlandish outfits. Most of the players were still undernourished and underweight. Some of them were almost passing out by the end of their matches."

Supplies were still scarce on French soil in 1946, and the black market was thriving, providing vegetables, lettuce and tomatoes, though meat, fish and even bread were hard to find. To fill the gaps, the top French players took part in as many invitation tournaments as possible in Switzerland or Sweden, which were less affected by the lack of food. The Americans meanwhile took all the necessary precautions before journeying to a Europe that was still reeling from the effects of the war. Jack Kramer crossed the Atlantic with plenty of fresh meat in his luggage, only to have it confiscated by customs upon arrival.

With the food shortages combined with six years without any competition, the Europeans certainly did not figure among the favourites for the relaunched Grand Slam tournaments. Not that it was easy to draw up a hierarchy among those present in mid-July 1946. There were those who had turned professional, among them Donald Budge, Fred Perry and Bobby Riggs.

For some, the journey was a bridge too far, ruling out appearances by Australians John Bromwich and Adrian Quist. Others had not returned from the front, including Henner Henkel, who died at Stalingrad. And there were those whose German passport ruled them out of all competition - even Gottfried von Cramm, despite being a fierce opponent of the Nazi regime.

It was anyone’s guess who would emerge from the crowd of unknown newcomers and old-timers who had seen their best years stolen away from them. At Wimbledon, it had been a member of the latter – Frenchman Yvon Pétra – who came through to take the silverware.

The "Americans amazons"

The Americans nevertheless seemed to be just ahead of the pack. Across the pond, planet tennis had continued to turn, shamateurism had become well structured, playing standards had risen and as such, they were ready to bag the various Grand Slam titles for the foreseeable future. This is what happened in the women’s draw at Roland-Garros, where the "Amazons" outstripped the competition. The title went to Margaret Osborne, defeating Pauline Betz in the final, with Louise Brough and Dorothy Bundy the semi-finalists, and this particular foursome also filled the slots in the final of the women’s doubles - with Doris Hart instead of Dorothy Bundy.

They may not have been the most exciting of players, but their dominance of the game was fascinating to see, and the defeat suffered by the sixth "star" Patricia Todd at the hands of the new French darling Nelly Adamson Landry in the Round of 16 was the only upset in a women’s draw which went entirely according to the form book. And with an all-American final in the mixed doubles – the trophy going to Budge Patty and Pauline Betz – the U.S. contingent monopolised three finals out of the five played at the tournament.

Pétra and Bernard restore a nation's pride

The only titles the Americans missed out on were the men’s singles and doubles, where they were downed by the French flair of Yvon Pétra and Marcel Bernard, cheered on by a partisan crowd. Having come within two points of defeat in the quarter-finals against Budge Patty, 32-year-old Bernard took the singles title on Saturday 27 July at the expense of Jaroslav Drobny, again in five sets."It was a well-oiled scenario and one that people liked. There had been the war, and the French Open was forced to stop. And along comes a Frenchman who battles back from two sets down. When I won in the end, there was such an ovation," Bernard said about the final.

The following day, he was back on court alongside Pétra to finish off the 1946 Roland-Garros in style, this time winning the doubles and again in five sets, again in front of a capacity Centre Court crowd. "Yvon and I celebrated my title at the ‘Chez Patachou’ cabaret in Montmartre, and we didn’t get round to going to bed that night,” says Bernard, explaining their mid-match lapse when they lost the third and fourth sets 6-0 and 6-1, and found themselves 5-2 adrift in the decider. They turned things around however to win 10-8, and the whistles of the crowd soon turned to cheers. "The stadium went mad!" Bernard grinned.

"We burned with an intense passion for the game"

"Having been deprived of tennis during the war years, we had a real hunger to play,"added Destremeau, who made the fourth round in the singles draw. "We burned with an intense passion for the game, which I personally never knew at any other moment in my life – before or since. And since we were seeing our companions and wives again, the crowd were cheering us on like we were old friends… It was quite an atmosphere, and it is no doubt that impetus which helped us compensate for a while for how we had fallen behind in sporting terms."

These surprise victories also served as a collective catharsis, and gave expression to the sense of pride which the country had regained. "Having been subjected to propaganda paid for by the enemy for the past four years, telling us that we were crumbling and finished as a people, we can be a little too inclined to lose belief in our strength and our force," wrote René Mathieu and P-R. Waltz in the editorial of Smash magazine in the final quarter of 1946. From the rubble of the war was written one of the finest, and most unexpected, pages of French tennis history.

ROLAND-GARROS

18 May - 7 June 2026

ROLAND-GARROS

18 May - 7 June 2026