The French Open stadium may not be named after a tennis champion, but Roland Garros certainly deserves his place in the history books.

Please upgrade to the latest version for best user experience.

You can also try using other popular browsers.

Update my browser

The French Open stadium may not be named after a tennis champion, but Roland Garros certainly deserves his place in the history books.

The French Open stadium may not be named after a tennis champion, but Roland Garros certainly deserves his place in the history books.

As astounding as it may seem, not many people know the full story behind the man whose name was adopted by one of the world’s most legendary tennis venues. Admittedly, it is rather unusual that the name of an aviator should be adopted for a tennis stadium. This is just one of the originalities in the French Open story, and a well-deserved homage to a man who was both a pioneer and a hero.

Roland Garros was not an avid tennis player, despite being a keen sportsman. When he was younger, he had a talent for football, rugby and cycling, a sport that helped get his respiratory system back to full strength after a bout of pneumonia when he was 12.

Born in Saint-Denis de la Réunion on 6th October 1888, Garros graduated from the HEC business school and founded his own company at the age of 21 – a car dealership not far from the Arc de Triomphe – before his life took a new direction in August 1909. Having been invited to the Champagne region by a friend, he attended his first air show and fell completely in love with these crazy machines. Since Garros never did anything by halves, he immediately bought a plane and taught himself how to fly before obtaining his pilot’s licence.

On 6th September 1911, two years after the birth of this all-consuming passion for aircraft, Garros broke his first altitude record, reaching 3,910 metres (just under 13,000 feet) after taking off from Houlgate beach. He took part in a series of air show and races, astonishing spectators with his bravery and inventiveness. He quickly became a star in the discipline, with hundreds of thousands of people in both Europe and South America flocking to watch him in action.

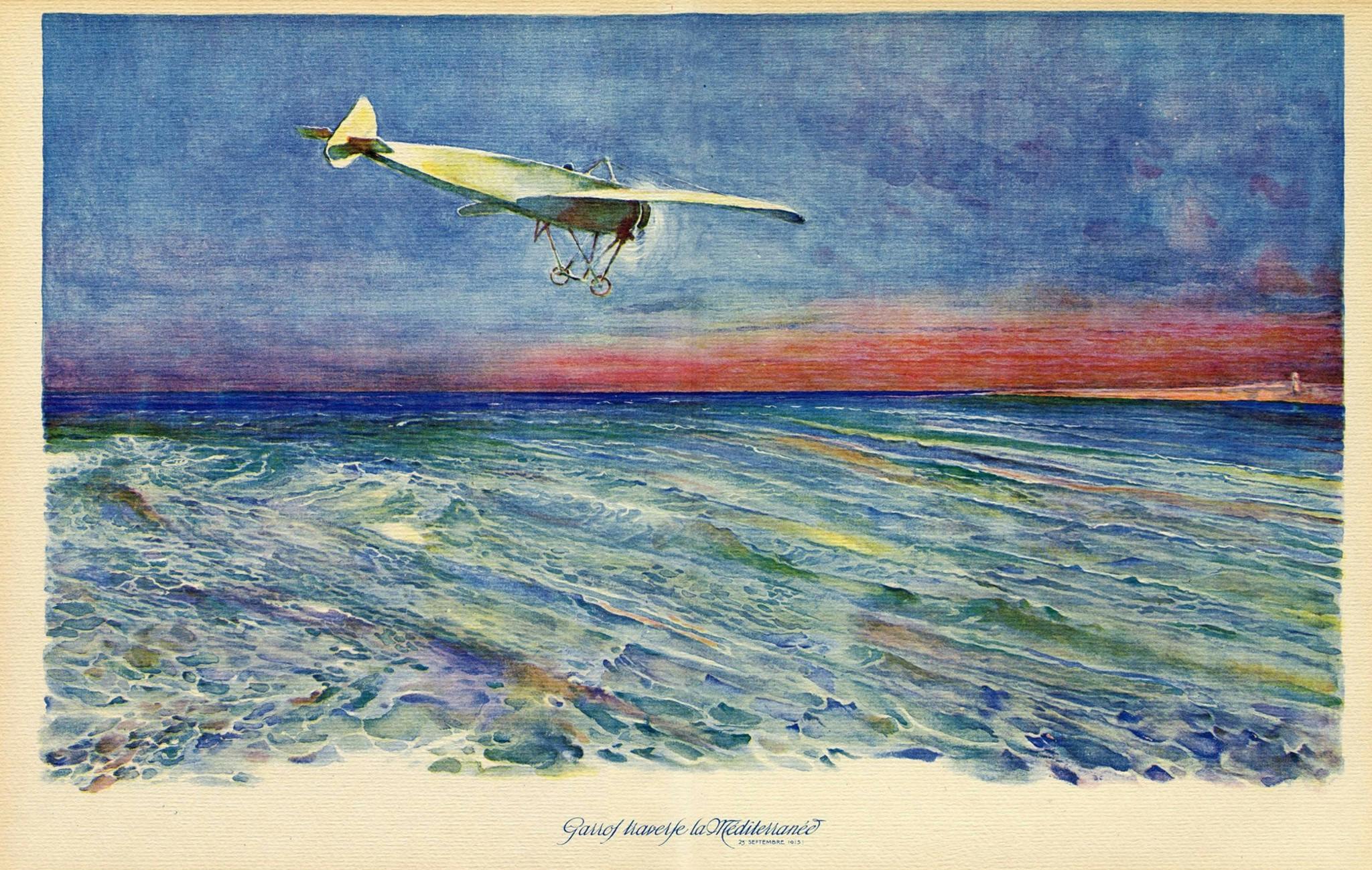

Roland Garros had great ambitions and wanted to fly over the seas. He set himself a new challenge: to cross the Mediterranean, something that had never been done at the time. On 23rd September 1913, he flew from Saint-Raphaël (French Riviera) to Bizerte (Tunisia) on his Morane-Saulnier monoplane. This epic journey would take nearly eight hours.

Setting off at 5.47am – with 200 litres of fuel and 60 litres of castor oil on board, and despite two engine failures that the mechanical genius managed to rapidly fix – Garros landed in Tunisia at 1.40pm after flying 780 kilometres (485 miles). He had just five litres of fuel left in the tank! This exploit made him the blue-eyed boy of the Parisian smart set. Jean Cocteau, among others, became a friend. The poet and filmmaker, who Garros sometimes took out in his plane, even dedicated a text to him: "Le Cap de Bonne Espérance" (The Cape of Good Hope).

When World War I broke out, the skilled pianist signed up to fight. At the time, planes were equipped with very little weaponry, if any at all. Roland Garros’ inventing and trailblazing skills kicked in and he developed the first single-seater fighter plane equipped with an on-board machine gun that fired through the propeller. It was revolutionary. He returned to the front equipped with his new firing device.

In early April 1915, sub lieutenant Garros notched up three consecutive victories in a fortnight, but was then hit by the German anti-aircraft defence over Belgium.

Forced to land, he was taken prisoner before he had chance to destroy his plane. His invention therefore fell into the hands of the enemy, who used his ideas to adapt their own aircraft.

It took strong-headed Garros three years to escape, clumsily disguised as a German officer. But his health had seriously deteriorated during his captivity. He had become severely short-sighted and had to make himself pairs of glasses in secret so that he could keep flying. Though Clémenceau wanted him to stay home as an advisor, stubborn Garros went back off to battle. This time, his bravery proved fatal: he was killed on 5th October 1918 over the Ardennes, though not before winning a fourth duel.

"Victory belongs to the most persevering." A quote attributed to Napoleon I and one which Roland Garros made his own... so much so that he inscribed it on his planes’ propellers. A phrase that could also be applied to the winners of the Roland Garros tournament…

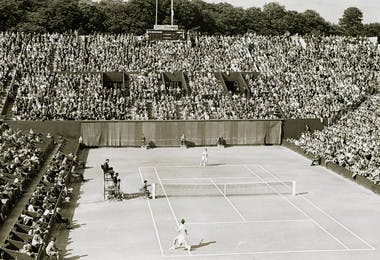

A First World War hero and trailblazer for aviation, Roland Garros was also a man who nurtured solid friendships. Ten years after his death, in 1928, the tennis stadium that had been built for the Mousquetaires to defend their Davis Cup title was named after Roland Garros, at the request of Emile Lesueur, president of the Stade Français and Garros’ former classmate at the HEC, whose campaign to chair the Stade Français had been supported by the pilot several decades previously.

So, yes, Roland Garros was only vaguely linked with the tennis world. But very few sports stadiums carry the name of a person who showed so much drive, intelligence and courage: cardinal values for anyone who hopes to reign supreme at the Porte d’Auteuil.